Impacts of Climate Change on California Forests

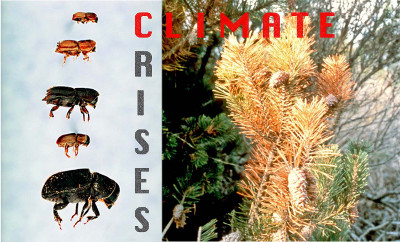

Bark beetles, pitch canker, and forest dieback

In large swaths of California forests, trees are dying from infestations attributable to climate change. According to the FAO, "some massive outbreaks of tree-killing forest insects may be attributed to climate drivers." In North America, vulnerable species include Fir (Abies), Juniper (Juniperus), Spruce (Picea), Pines (Pinus), Poplar (Populus), Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga), and Oaks (Quercus).

Research by the California Dept. of Forestry and others indicates that many species of bark beetle carry fungus (Fusarium circinatum Nirenberg & O’Donnell) that infects trees with pitch canker disease, leading to forest dieback. At least ten California counties report infestations, particularly Santa Cruz and Alameda.

Forests central to cap-and-trade

California’s landmark law to limit greenhouse-gas emissions, A.B. 32, is now being implemented as the state's Air Resources Board (ARB) puts in place rules and procedures (“protocols”) to meet the law's objectives.

Forest protocols are a key element in the cap-and-trade program developed by the ARB to allow the buying and trading of carbon “offsets.” Sustainably managed forests are a primary source of these offsets.

Environmentalists cried foul when the ARB announced it had adopted forestry protocols that would allow timber companies to reap millions of dollars by selling “sustainable forestry” offsets even as they clearcut forests as usual. Only sustainable forestry practices above and beyond clearcutting as usual should be credited as offsets.

A multitude of forest impacts

Scientists have long sounded warnings about the potential impacts of global warming on forests in California. According to Global Climate Change and California: Potential Impacts and Responses (ed. Joseph B. Knox and Ann Foley Scheuring, University of California Press, 1992), possible climate change impacts on California forests include:

- elimination of Douglas-fir from lowlands due to loss of winter chill conditions needed for germination and growth;

- widespread movement of forests upslope from their present locations;

- increased productivity of redwood in northern areas, but reduction of redwood range in southern areas if precipitation decreases;increased rates of decomposition and nutrient release from litter;

- succession in forest gaps by shrub species such as ceanothus and alder, leading to an increase in spatial vegetation diversity;

- wildlife habitat changes favoring species that take advantage of gaps and dead wood;

- likely deterioration of stream water quality due to increased rates of decomposition, weathering and erosion caused by tree mortality.

Nearly a decade ago, the National Academy of Scientists, using computer models to forecast the possible effects of climate change on California ("Emissions pathways, climate change, and impacts on California"), predicted that by the end of the century alpine and subalpine forests in California would be reduced 50%-75% under the best-case scenario, and 75-90% in the worst-case scenario. Snowpack in the Sierra would be reduced 30%-70% in the best case and 73%-90% in the worst case, "with cascading impacts on runoff and streamflow" that "could fundamentally disrupt California's water rights system."

Water

Water is key in California. Even without the many other disruptions from climate change, the state’s water resources have been stretched to the limit. Changes in the amount of precipitation the state receives, and, crucially, the amount it can use, will affect agriculture, urban populations, wildlife and forests.

Confronting Climate Change in California, a 1999 report put out by the Union of Concerned Scientists and The Ecological Society of America, predicted that Californians will see much warmer, wetter winters and only slightly warmer but much drier summers as the most likely result of continued global warming.

With warmer winters, more precipitation will fall as rain than as snow, and this will affect the flow of rivers and streams in the state. Since the soil quickly becomes saturated in winter, the additional rainfall will mean more runoff. And since there will be less snow, there will be less snowmelt in spring and summer, leading to lowered river and stream flows and drier conditions downstream.

Shifting ecosystems

An important effect of increasing temperatures will be the changes in ecosystems as plant and animal species succeed or fail in migrating to stay within suitable climate.

"Climate change will inevitably shift the suitable range for each type of ecosystem, as well as the mix of plants and animals at the vital focus of energy and nutrients that occur within them." —Confronting Climate Change in California.

But some species may not be able to migrate if suitable habitat no longer exists. Species adapted to an alpine climate, for instance, might not be able to find comparable conditions in a warmer world.

"…5 percent to 10 percent of California native plant species would no longer find suitable temperature conditions within the state if average temperatures warmed 5 to 6 degrees F." — Confronting Climate Change in California

And in the most populated state in the country, a considerable amount of habitat has been fragmented by development—urban sprawl, ranches, vineyards, farms, highways. So even if suitable habitat exists somewhere, species may be blocked in their attempts to migrate to it.

More fires

Another consequence of hotter drier summers could be a rise in the frequency and severity of forest fires in California. As the state heats up, forests will tend to shift northward and uphill to cooler climes. Many scientists fear the forests may not be able to migrate rapidly enough, leaving large areas of dry, dying trees susceptible to intense blazes.

A hotter, drier climate, with more Santa Ana winds and drier summers, might well lead to more fires in Southern California forests.

"In dying forests, the threat of fire becomes much greater, and intense wildfires may become more frequent, widespread and destructive," says a report by the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis titled "Climate Change and Variability in California."

Changes in rainfall and water flow could cause drought conditions in some parts of the state. Without sufficient water, forests would also be stressed and more vulnerable to damaging insects such as pine bark beetles.

Storms

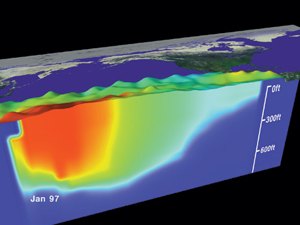

A rise in "El Niño-like" storms, and consequent increased flooding in coastal and delta areas, is predicted by several studies.

It is also possible (though by no means certain) that changes in surface ocean temperature could affect the frequency and density of coastal fog. If this scenario came to pass, coastal redwoods, which get a good deal of their annual ration of moisture from fog, could eventually disappear from the coast ranges.

In the case of long-lived trees such as the redwoods, the damage might not be immediately apparent.

"Individual redwoods may survive for centuries, even millennia," according to Confronting Climate Change in California, "long past the point where climate changes make growth of new seedlings impossible."

These doomed forests are known as "museum" populations, wherein individual trees seem healthy, but are no longer able to reproduce.

Gains and losses

The increase in carbon dioxide, and the increased average temperatures, could actually increase forest productivity, at least in the short run. But drier climate, changes in water flow, increased frequency and severity of forest fires, and increased vulernability to pest outbreaks could cancel out these gains.

Responding to the challenge

California state agencies on the front lines of global climate change have been devising ways to respond to these changes.

The California Air Resources Board is responsible for coordinating climate change issues in the state and implementing the state's cap-and-trade program. The agency's webpage lists the various state agencies and programs that are attempting to respond to global climate change.

The California Department of Forestry has announced its intention to preserve the carbon storage capabilities of woodlands under its control. The agency says it plans to retain older, larger trees, since these have the greatest carbon storage capacity. (How this will play out in light of the CDF's historical propensity to cater to the timber industry, and to pad its own budget through logging projects on state forests, is yet to be seen. Industrial logging could be given cover by "fuels management" and "thinning " projects undertaken as part of a global-warming response.) The agency also is involved in urban forestry, and works with private landowners, advising them on how to maximize carbon storage capacity in their woodlands.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife, anticipating the dislocation of habitat that will be caused by global warming, is taking an ecosystem approach in its conservation planning, trying to protect large areas containing a diversity of habitats to allow for migration of species faced with habitat change.

What You Can Do

Global climate change is happening now. The international community is still not unified in its response, but given the serious long-term consequences of inaction, we should do whatever we can, as soon as we can.

The shrinking of the ozone hole that has followed adoption of the Montreal Protocol's limits on CFC emissions shows that human actions can reverse large-scale environmental problems.

What actions can we take to help avert global warming? What strategies should be put in place to mitigate the effects of sudden climate change?

The first thing we all can do is to make sure our government representatives understand the importance of global warming. Support pubic officials who demonstrate an awareness of the problem. Let your representatives know that you are concerned, and are willing to vote that concern.

Actions against climate change:

Limit fossil fuels: Use fuel-efficient vehicles. Promote mass transit alternatives. Promote alternative energy sources (solar, wind, fuel-cell). Oppose heavy hydrocarbon-releasing projects such as the Keystone Pipeline from Canada and hydrofracking for natural gas.

Limit development: We need to preserve as much forest as we can, both as a carbon sink, and to provide habitat corridors for species migrating in response to global warming. Fighting sprawl development can both help preserve wild lands and cut down on the use of fossil fuels.

Plan for the future: Design nature reserves to accommodate future climate change, provide wildlife migration corridors. Restore degraded habitat.

Educate yourself: Learn all you can about the causes and potential effects of global climate change.

Clearcutters Hop on Cap-and-Trade

©2025 Forests Forever. All Rights Reserved.